For the argument that SML contributed to the increase in petroleum consumption, and therefore taxes (to the tune of 2.4 billion GHS), to be sustainable, proof has to be shown that SML’s interventions have led to an uptick in volumes recorded over and above the historical trend of increases over time.

What the data instead shows is a correlation between volume increases or decreases and exogenous (external) economic factors. That is simply to say, several factors, other than any work SML may be doing, have bigger effects on whether Ghanaians buy and use more petrol or diesel in any particular period.

Take, for instance, the fact that more residual fuel oil (RFO) was consumed in Ghana in 1999 than in 2022. The demand for this fuel was historically boosted beyond its traditional importance in the marine industry due to its use in legacy equipment in the industrial sector. As other petroleum products supplanted RFO, however, volumes dropped significantly. Following a very similar trajectory, the volume of kerosine consumed in Ghana in 2022 was 30 times less than that consumed in 1999, obviously, in part, because of the rise of LPG. Indicative of the challenges in Ghana’s fishing sector, premix fuel consumption has halved over the last ten years. Aviation fuel consumption in 2012, seven years before the SML contract was signed, was nearly 10% higher than in 2020, the first year after the SML monitoring regime went into effect. It is not hard to understand why: COVID.

Clearly, there are broad, and exogenous, factors impacting fuel demand, consumption, and, thus, volumes than can be easily, and mistakenly, subsumed under the ambit of regulatory monitoring and whatever magic SML claims to be performing in the sector.

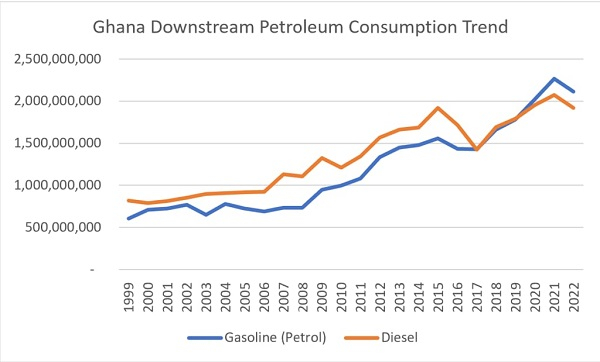

Focusing only on gas oil (“diesel”) and gasoline (“petrol” or “premier motor spirit”), the main fuels consumed in the downstream sector, elicits the same trend: consumption rises steadily, punctuated mainly by factors exogenous (external) to the fuel industry and its regulation (see chart below).

For example, petrol consumption was steady for much of the decade between 1999 and 2009 until the completion of HIPC, the discovery and commencement of oil production, and the completion of the 2015 – 2019 IMF program, combined to trigger an economic mini-boom. The surge in consumption continued until dumsor (Ghana’s perennial power crises) peaked in 2015, leading to a major cratering of volumes. The mini-boom created by the end of dumsor, the completion of the IMF program, and the return to the Eurobond market with a vengeance, accounts for the last spurt of growth that just ended in 2022.

If we were to take the claim at face value that increase in petroleum consumption and the corresponding taxes are due to the handiwork of SML, then we would also have to penalise SML for any drop in consumption volume, such as we saw between 2021 and 2022 for gasoline and diesel.

As far as tax increases are concerned, the "SML is responsible" argument is even more ridiculous since, besides volumes, pricing is a major determinant of how much taxes the government rakes in. Ghana has at various times had ad valorem and ex depot price based taxes that link the price at the pump to the tax revenues of government.

Is SML in any way responsible for price changes at the gantry, depot, or pump levels? How then does one isolate the effects of pricing from historical tax revenue trends (before and after SML's intervention) to isolate the specific contribution of SML's work? Only through the kind of sophisticated statistical work done by the likes of IMANI and ACEP can that be done. And that statistical work has conclusively proven that SML has had no effect on tax revenues.

See Bright Simons's full article here

Opinions of Thursday, 25 April 2024

Columnist: Bright Simons