Introduction

Whistleblowing is a fundamental pillar in the fight against corruption. It allows individuals to expose wrongdoing and hold those in public offices accountable. However, the way a country handles whistleblowers defines its commitment to transparency, justice, and the rule of law.

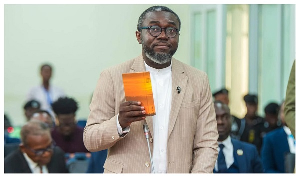

The current case involving Oliver Barker-Vormawor, who has accused the Chairman of the Appointments Committee, who doubles as the First Deputy Speaker of the Ninth Parliament, and some NDC members of Parliament who serve on the Appointments Committee of accepting bribes from His Excellency President Mahama’s appointees, raises serious concerns about Ghana’s approach to handling whistleblower allegations.

Instead of launching an independent investigation, the same committee accused of corruption is interrogating the whistleblower. This is a blatant conflict of interest that undermines the credibility of the investigation.

This is not the first time Ghana has mishandled a whistleblower case. A similar incident occurred during the His Excellency President Akufo-Addo administration, when the current Majority Leader of the ninth Parliament and member of Parliament for Bawku Central, Hon. Mahama Ayariga, accused some members of the NDC MP(s) on the eighth Parliament Appointments Committee of taking bribes from former President Akufo-Addo’s appointees, only for the matter to be resolved with a mere apology.

A Troubling Precedent: The Mahama Ayariga Case

In 2017, Hon. Mahama Ayariga, then an NDC MP for Bawku Central, alleged that the Chairman of the Appointments Committee, Hon. Joseph Osei Owusu, and Minister-designate for Energy, Boakye Agyarko, had attempted to bribe MPs on the committee to approve Agyarko’s nomination.

The matter was referred to a special bipartisan committee, which later determined that there was no credible evidence to support Ayariga’s claims. However, instead of pursuing legal action against him for making false allegations, he was simply asked to apologize.

This approach was deeply flawed for several reasons:

1. If the allegations were true, a mere apology was not enough—the officials involved should have faced legal consequences.

2. If the allegations were false, Mahama Ayariga should have faced prosecution under Section 3(3) of the Whistleblower Act, 2006 (Act 720) for making false claims.

3. The lack of a transparent, independent investigation weakened public confidence in Parliament’s ability to hold its members accountable.

The Mahama Ayariga case set a dangerous precedent that corruption allegations against high-ranking officials can be easily dismissed without proper legal scrutiny. This same trend appears to be repeating itself with Oliver Barker-Vormawor.

The hasty acceptance of an apology from a whistleblower without a thorough, independent probe suggests that Parliament is more interested in protecting its members than in ensuring accountability.

The Role of the Special Prosecutor and the OSP Act in the Case

The Office of the Special Prosecutor (OSP) was established under the Office of the Special Prosecutor Act, 2017 (Act 959) to independently investigate and prosecute corruption-related offenses.

Key Provisions of the OSP Act

1. Section 2(a) of Act 959 states that the OSP is to:

“Investigate and prosecute cases of alleged or suspected corruption and corruption-related offenses under the Public Procurement Act, 2003 (Act 663), and any other corruption-related offenses under any other enactment.”

2. Section 3(1)(a) empowers the OSP to act “on its own initiative or on a complaint made by a person or authority.”

3. Section 3(3) states that the OSP is independent and “shall not be subject to the direction or control of a person or an authority in the performance of its functions.”

Given these clear mandates, why has the OSP not initiated an investigation into this bribery allegation? The OSP’s silence on this matter raises doubts about its effectiveness and independence. A proactive Special Prosecutor should have stepped in to investigate these claims instead of allowing Parliament to handle the case internally.

Relevant Provisions in the Whistleblower Act, 20016 (Act 720)

The Whistleblower Act, 2006 (Act 720) provides protection for individuals who disclose corrupt acts. However, it also sets clear guidelines on handling false allegations:

1. Section 3: A whistleblower may make a disclosure to a person or institution if they have reasonable cause to believe that corruption or an offense has been committed.

2. Section 12-19: Protects whistleblowers from victimization and retaliation as a result of their disclosure.

3. Section 20-25: If a whistleblower’s report leads to a successful conviction, they may be entitled to a reward determined by the Attorney General.

If an allegation is found to be false and made in bad faith, the whistleblower has to face criminal sanctions for misleading authorities especially when it is established that the whistleblower submitted the allegation out of malice.

The Act 720 urgently requires a twofold responsibility. Whistleblowers must act in good faith, and institutions must also ensure a fair and independent investigation. Based on the Committee’s hearing today, both the Whistleblower and Parliament have failed to demonstrate true commitment to combatting corruption.

How Advanced Democracies Handle Whistleblower Cases

In democratic countries with strong anti-corruption institutions, whistleblower allegations are investigated independently to ensure fairness and credibility.

United States (Whistleblower Protection Act, 1989):

1. The Office of Special Counsel (OSC) independently investigates claims.

2. Whistleblowers are protected from retaliation under the law.

3. If allegations are proven false, legal consequences follow, but only after a thorough, fair process.

The Watergate Example:

A good example of how an advanced democracy handled corruption allegations is the Watergate scandal in the United States (1972-1974).

In that case, FBI Associate Director Mark Felt (alias “Deep Throat”) leaked information that exposed President Richard Nixon’s involvement in illegal activities, including spying on political opponents.

How the U.S. Handled the Case:

1. The U.S. Congress launched an independent investigation through the Senate Watergate Committee, not a committee made up of Nixon’s allies.

2. The FBI and the Special Prosecutor’s Office conducted thorough investigations, ensuring that justice was served.

3. The investigation uncovered clear evidence of corruption and obstruction of justice, forcing President Nixon to resign in 1974.

4. Several high-ranking officials were prosecuted and jailed, proving that no one was above the law.

The Watergate scandal teaches us an important lesson: When public officials are accused of corruption, there must be independent oversight to ensure a fair investigation.

Ghana should follow this example by forming an independent probe into lawyer Oliver Barker-Vormawor’s allegations rather than allowing the accused committee to investigate itself.

This highlights the core problem with Ghana’s approach because allowing the Appointments Committee to investigate itself violates fundamental principles of fairness. A truly independent body should handle the matter.

The Jussie Smollett Case (U.S.)

In 2019, Smollett, an actor, falsely reported to the police that he was the victim of a racist and homophobic attack. This story, which garnered national attention, later proved to be a fabricated narrative. Smollett staged the incident with the help of two men, making false statements to the authorities. His claim was later proven to be a deliberate act of malice.

After an extensive investigation, Smollett was charged with multiple counts of disorderly conduct for filing a false police report. In 2021, a jury found him guilty, and he was sentenced to 150 days in jail and ordered to pay restitution for the costs incurred by the police investigation, as well as additional fines.

This case highlights how advanced democracies, such as the U.S., punish whistleblowers who act out of malice and deceit.

A Call for Accountability and Reform

To ensure transparency and restore public trust, the following actions must be taken:

1. Establish an Independent Probe – Parliament should set up an ad hoc investigative by-partisan committee separate from the Appointments Committee.

2. OSP Must Act – The Special Prosecutor must initiate a formal investigation under Sections 2 and 3 of Act 959.

3. Fair Legal Consequences – If proven, officials involved should be prosecuted under Section 252 of the Criminal Offenses Act, 1960 (Act 29) for bribery. If false, the whistleblower should be held accountable under Section 3(3) of Act 720.

4. Strengthen the Whistleblower Protections – Parliament should amend Act 720 to provide stronger protection for whistleblowers against institutional bias and severe penalties to whistleblowers whose actions are based on malice.

Conclusion

The handling of corruption allegations in Ghana remains deeply flawed. The cases of Mahama Ayariga and Oliver Barker-Vormawor show a troubling trend that whistleblowers are either forced to apologize or subjected to intimidation, while real accountability remains elusive.

If Ghana truly wants to combat corruption, it must:

1. Ensure independent investigations.

2. Empower the OSP to act decisively.

3. Hold both corrupt officials and false whistleblowers accountable.

Over 57% of Ghanaians have voted for His Excellency the President John Dramani Mahama and the NDC government to reset the country on the right path. We will not accept setting for resetting.

The fight against corruption cannot be selective. Ghanaians must demand accountability, transparency, and fairness in all corruption investigations regardless of political affiliation.

Opinions of Friday, 31 January 2025

Columnist: Gideon Buabeng Adu