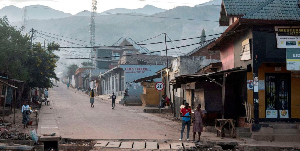

Ebola, extremism and elections compound growth problems faced by many in the sub-Saharan region, writes William Wallis

Sub-Saharan Africa's progress towards greater economic self reliance and political stability has been underpinned at most times over the past decade by favourable external conditions. With world prices softening for the raw materials many African economies rely on for export earnings, the cost of debt rising on international markets and western donor funding coming under strain, the surpluses of the last decade can no longer be assured. "It has been easy to be bullish about Africa with commodity prices going up," says Charlie Robertson, chief economist at Renaissance Capital, the Russian investment bank that has championed African growth. "[Falling commodity prices are] now the biggest challenge to the Africa-rising thesis," he says. There is still a wall of money eager to exploit commercial opportunities in Africa's underdeveloped markets — exemplified by the record private equity fund of $1.1bn raised by Helios Investment Partners, the London-based fund specialising in African investments, earlier this month. But in a more constrained global environment African governments may have to work harder to sustain the momentum; 2015 looks set to be a testing year. On the continent's western flank, Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone are still struggling to contain the worst ever outbreak of the Ebola virus, with more than 8,000 dead since early 2014 and billions wiped off the value of their economies. Health officials are predicting that it could be another year before the epidemic is fully contained. Another epidemic, of Islamist extremism, is weighing on the largest economies in the east and west, with security forces in both Nigeria and Kenya struggling to contain a terrorist onslaught. Meanwhile a heavily charged election timetable, with polls due in more than 10 countries, ensures a turbulent year of politics ahead. The more so, because there will be less money to paper over cracks. Many economists and investment analysts point out that the continental renaissance of the last decade was not just about commodities. It was about smart policy choices, improved macroeconomic management, sounder balance sheets, in the wake of western backed debt relief, and a boom in consumer spending. Nevertheless the rising tide that floated all boats was causing soaring demand for raw materials, sustained by the growth of China. In the next chapter, says the Zambian economist and writer Dambisa Moyo, poorer performing countries will be more exposed, while those that improve the competitive environment for investment are more likely to prosper. There are some obvious winners and losers already. Zambia has been exposed by the falling price of copper on which it depends for the vast majority of its foreign currency earnings. The downturn in mining has been compounded by a government decision — taken during the boom — to bring in legislation due to take effect this month to raise the gross royalty on mines from 6 per cent to 20 per cent. Barrick Gold has announced the suspension of activity at its Lumwana copper mine as a result. The collapsing price of oil is a more mixed blessing. The continent's largest economy, Nigeria, faces a tumultuous period with tense elections due in February, at a time when state revenues, more than 70 per cent of which come from oil, have halved. The development of recent oil finds in east African countries will also be delayed. However, for the continent's net oil importers, lower energy costs, and smaller import bills could prove a valuable boon, says Steve Kayizzi-Mugerwa, the African Development Bank's chief economist. Mr Kayizzi-Mugerwa believes that rapid urbanisation and the emergence of a new class of consumers in many African cities will sustain the growth story, while large-scale infrastructure investment such as the $10bn Chinese-backed railway from Mombasa inland into Kenya will continue to open up the region. But Renaissance Capital's Mr Robertson says for African economies to gain access to the capital needed to spark industrialisation, they will have to offset effects of falling commodity revenues. In addition, although sub-Saharan African economies have grown fast over the past decade, most have failed to come close to creating enough jobs for young people entering the market. To do that, says David Ndeye, a Kenyan economist, governments will have to become far more strategic about how they use scarce resources, encourage the development of skills and make their economies competitive. He says: "For transformation you need a coherent and proactive policy agenda. That you don't have. Most of us are free wheeling."

Opinions of Wednesday, 4 February 2015

Columnist: Addo, Kofi