At least 93 countries have an acute teacher shortage and need to recruit some four million teachers to achieve universal primary education by 2015, a new United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation policy paper has revealed.

Prepared by UNESCO’s Institute for Statistics (UIS) and the EFA Global Monitoring Report (GMR), it said a quality universal primary education will remain a distant dream for millions of children living in countries without enough trained teachers in classrooms.

Under pressure to fill gaps, the report said many countries are recruiting teachers who lack the most basic training, citing the UNESCO Institute of Statistics (UIS) data, which said in one-third of countries with data, fewer than 75 percent of primary school teachers were trained according to national standards in 2012.

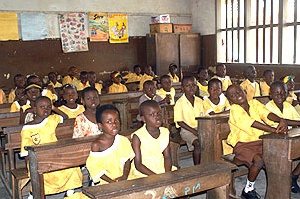

A developing country like Ghana has an about-60,000 teacher deficit at the basic level, and the country's efforts to achieve the targets of Universal Primary Enrolment and Completion by 2015 as enshrined in the Education for All Protocol -- to which the country is a signatory -- could be challenged.

During the academic year 2011/2012, the pupil-teacher ratio in Ghana was 25:1 at the basic private school as compared to 29:1 at the public basic school.

In the rush to fill the chronic global shortage of teachers, the UNESCO policy paper -- which was published on World Teachers Day 2014 -- said many countries are sacrificing standards and undermining progress by hiring people with little or no training.

“Putting well-intentioned instructors in front of huge classrooms and calling them teachers will not deliver our ambitions to have every child in school and learning,” said Aaron Benavot, Director of the EFA Global Monitoring Report.

“We have prepared a new Advocacy Toolkit for teachers to help us relay these messages to their governments. Teachers -- better than anyone else -- can relay how teacher-shortages and lack of training are making it near-impossible to deliver quality education.”

If the deadline of achieving universal education is extended to 2030, more than 27 million teachers need to be hired; 24 million of whom will be required to compensate for attrition, according to UIS data.

At present rates, however, 28 (30%) of these 93 countries will not meet these needs. Sub-Saharan Africa faces the greatest teacher-shortage, accounting for two-thirds of the new teachers needed by 2030. The problem is exacerbated by a steadily growing school-age population, according to the UNESCO report.

It said countries must ensure that all new teacher candidates have completed at least secondary education. Yet the GMR shows that the numbers of those with this qualification in many countries are in short supply: eight countries in sub-Saharan Africa would have to recruit at least 5 percent of their secondary school graduates into the teaching force by 2020. Niger would need to recruit up to 30 percent.

In sub-Saharan Africa, the cost of paying the salaries of additional teachers required by 2020 totals an extra US$5.2billion per year, according to UIS projections, before counting for training, learning materials and school buildings.

With the greatest number of children out of school in the world, Nigeria alone will need to allocate an extra US$1.8billion per year.

“The good news is that most countries can afford to hire the extra teachers if they continue to steadily increase investment in education,” said Hendrik van der Pol, director of the UNESCO Institute for Statistics.

“Over the past decade, education budgets across sub-Saharan Africa have been growing by 7% in real terms, reflecting the commitment to get more teachers and children in classrooms.

However, four countries will need to significantly increase their education budgets if they’re to cover the bills and provide training to new recruits: the Central African Republic, Mali, Chad and Malawi.”

Regional News of Monday, 13 October 2014

Source: BFT