Rod McLaren's journey has taken him from hardware store owner in small town Saskatchewan to African chief in Ghana.

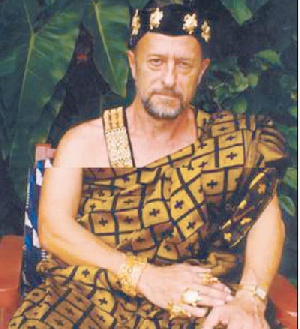

Bespectacled and bearded, the 58-year-old looks the part of a sophisticated professor -- that is, until you see him wearing a Kente wrap and gold regalia.

And it's not Rod McLaren anymore -- he now goes by Nana Akwasi Amoako Agyeman.

"Those are names given to me (by higher-ranking chiefs in the region). They are associated with great power and not given out lightly," McLaren said in a telephone interview from Busua, on the Gulf of Guinea. His official title is development chief or king, an appointed position overseeing the economic and social growth of 38 villages. It's a long way from his boyhood home on a farm 22 kilometres north of Maidstone. The path to royalty began after graduating from the University of Saskatchewan with an English degree. McLaren headed for Ghana in 1971 to teach English literature on a two-year contract with the Canadian development organization CUSO. During that time he met his future wife, Comfort. He returned to Canada in 1973 and wrote her letters, not knowing they had never reached her as she had left her home village. In 1976, he went back to Ghana, found Comfort, proposed, got married and moved back to Saskatchewan, all within a few weeks. "I was young and I was crazy and I was in love. He saved his money and travelled all the way from Canada to ask me to marry him. I couldn't possibly say no," said Comfort, whose first steps in Canada came in the middle of February. "It was the first time I ever saw snow. Everything was white -- the trees, the houses," she said. "Sometimes I feel like I'm back in Saskatchewan," Comfort added. "It's the winter season here (in Ghana) and my joints are aching and it's cool out." That "cool" temperature in Ghana on Thursday was 28 C. That's not exactly Saskatchewan weather, but it's enough to bring back memories, she said. The couple lived a few years on a First Nations reserve, where McLaren taught school and then moved to a farm near where he grew up. The couple tried farming, but gave it up and opened a Home Hardware store in Maidstone. After 22 years away from Ghana's sun and beaches, they sold the business and went back with their three Saskatchewan-born children in 2001. But in many ways, the Canadian Prairies are still with them. McLaren followed the Canadian Olympic team's success in 2006 and can't shake his affection for beer -- although he's drinking Ghanaian brew now. He certainly doesn't miss plugging in a car and shovelling snow, but it's not easy to find a "good, juicy T-bone steak." McLaren applies the sense of community and concern for others so ingrained in someone raised in a small town to his new role. "I put a lot of energy into working for the betterment of the people," he said. "Ghanaians are known for their friendliness and in that way, (they) share something in common with Saskatchewan people." Like many African countries, Ghana remains heavily dependent on international financial and technical assistance. As with many former British colonies, the country is wealthy but the people are poor, he said. McLaren has been raising funds to build a daycare in one village and is aiming to tackle the dearth of training for teachers in the region. "Many teachers have, at best, a high school education and not a very good one at that," he said. He also wants to take advantage of a vast supply of oil palms, turning them into a supply of biodiesel fuel, which could boost the area's economy. "We're very dependent on outside fuel sources, but I think there's a lot of potential here to become self-sufficient," McLaren said. His role as chief is not a paid position, but rather a lifetime appointment that carries great prestige -- as long as he doesn't mess up. It was offered to him three times before he finally accepted, after seeking advice from other chiefs. Despite being Caucasian and Canadian, there was never any backlash to his appointment, McLaren said. "The people are so warm and welcome and generous. I've always felt at home here," he said. "The people call out and greet me. They trust in the ability of my wife and I to bring good things to their communities. "I never thought when I worked for (First Nations) chiefs in Saskatchewan that I would be one myself," he added with a laugh.His income comes from the African Rainbow Resort he owns and operates with his family. It was designed by McLaren's son and built by the skilled labour of their extended Ghanaian family members.

Again, his roots tend to show in running the resort. On Thursday, he sipped a beer and shot billiards with Australian guests. The hospitality of operating a hardware store that "prided itself in providing great service (and) friendly advice" has been extended to McLaren's new endeavours.

"Not a day goes by that I don't think of the journey I've taken. It's been a great time and continues to be so."